The Great Cultural Death Drive

This season’s It girl is a ghoul.

A notable cultural convergence happened last week: New York City Fashion Week, the arrival of Ryan Murphy’s salacious new TV show about John John and Carolyn Bessette, and the premiere of Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights adaptation. All three of these things have been battling allegations of infidelity to source material, to reality, and to fans. Notably, it’s never been more en vogue to dress like you know your imminent and tragic fate. From runway to screen, the doomed heroine has been exhumed.

You can’t scroll anywhere without bumping up on a photo of Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, resplendent in Calvin Klein and Yohji Yamamoto. She is contemporary fashion’s ultimate muse: forever gamine, made compelling by tragedy, and never subject to the unchic parts of life like aging, divorce, childrearing, career failure, or being forced to talk on camera.

For the recent FIT exhibition “Dress, Dreams and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis” Lacanian psychoanalyst and curatorial consultant Dr. Patricia Gherovici told The Guardian that “fashion is a way of dressing up the death drive.” Originally conceived by Sigmeund Freud, the death drive is a subconscious longing for death that finds its relief in forms of self-destruction and aggression towards others (why someone smokes, or engages in a sadomasochistic relationship).

Cathy’s costuming in Wuthering Heights is exactly that drive manifest, treated with a distractingly libidinal attention: blood red latex, pink pearlescent tissue paper. The fashion conveys exactly what is happening at any given moment—a black mourning veil and white satin shroud make for a ghoulish subversion of the bridal veil. Even if you haven’t read the book, even if you have been sitting in a padded room with wax stuffed up your ears, you already know her fate through her fashion.

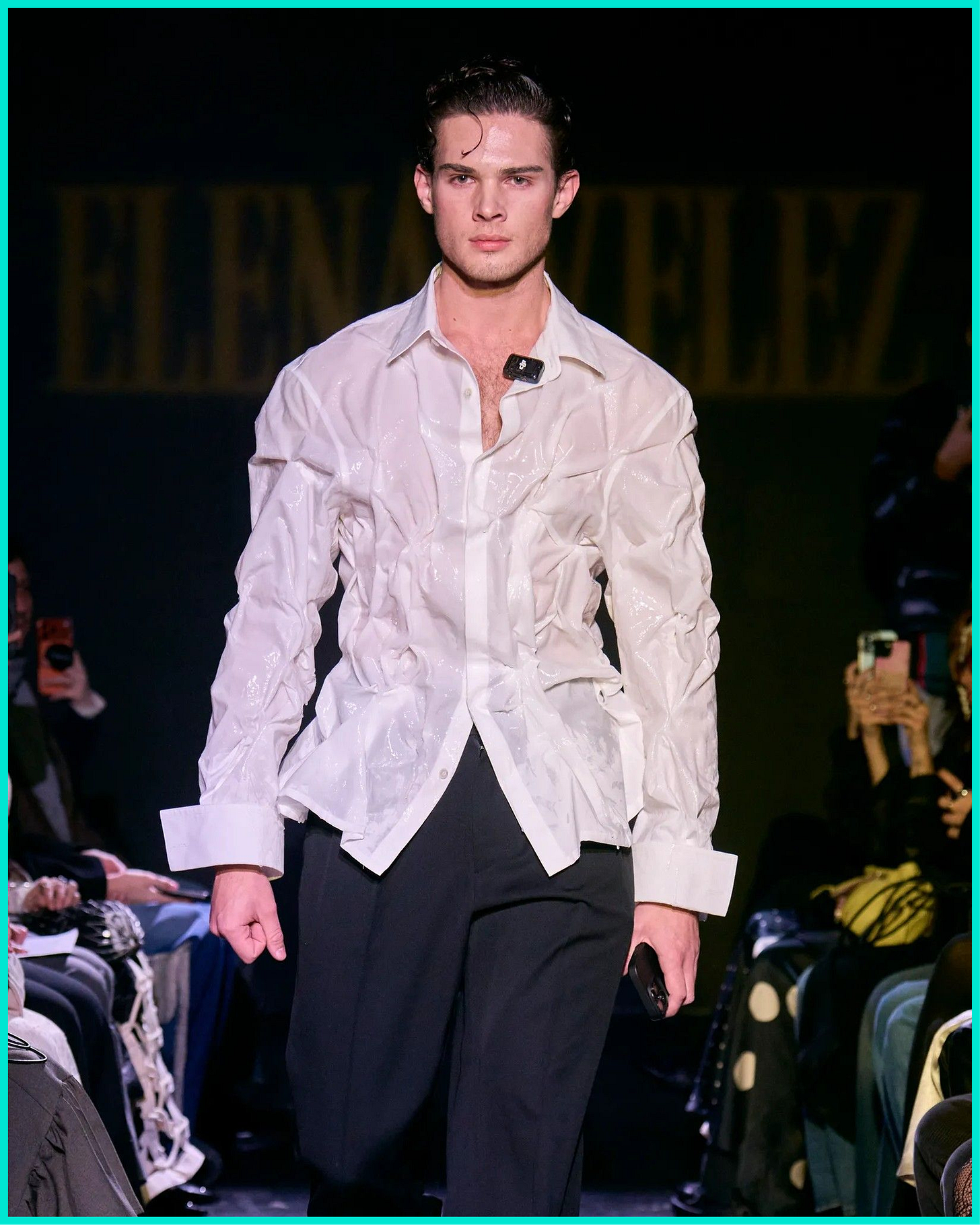

Meanwhile at fashion week, there was Sandy Liang’s take on Marie Antoinette, Anna Sui’s offerings of ghostly heiress chic and Edie Sedgwick bohemian, and Andrew Curwen’s corseted collection “Nocturnal Conditions” where models sported smears of black eyeshadow and purple lipstick. Some designers even took on the death drive literal. At Calvin Klein (the sartorial home of Bessette) designer Veronica Leoni focused on “the cult of the body”—a controlled, thin body, of course. At Elena Velez, where interest in clothing is secondary to stunt casting, the death drive walked the runway: Clavicular, a streamer best known for injecting himself with various substances (like meth) in the name of good looks, and anorexia nervosa influencer Liv Schmidt.

For i-D’s last spring issue resident Rickophile Steff Yotka wrote what will become known as a defining profile on Rick Owens. Declared the “Lord of Darkness” by fans, Owens’ work happily resides in the ghostly otherworld. In the interview he tells Steff, “My gloomy pursuit of transcendence has been part of the Symbolist culture of Paris since Gustave Moreau’s time.” Unlike other designers, Owen’s approach has always been one grounded in symbolism (central to symbolism is the exploration of death as a way to escape the world), and an earnest pursuit of immortality. Is that what this preoccupation with resurrecting the dead is actually about? Achieving one’s own immortality…or at least attempting to have some type of control over legacy.

This relationship between fashion, photography, and social media, interacting with life primarily through a medium preoccupied with death, isn’t necessarily new but does happen to be reaching a boiling point. In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” Walter Benjamin references the nature of early photography as a way to capture and preserve the dead. In the same text Benjamin writes of “aura”, the insubstantial quality that makes something significant, and the way photography degrades it. (Aura happens to be the word of the moment—“aura farming,” the act of cultivating it, was shortlisted for Oxford Dictionary’s word of 2025, losing out to “rage baiting,” though why the word of the year would be two words is beyond me.)

Everything today is conveyed to us through images—we don’t experience the world directly. Not only are we working in a dead medium, the images themselves evaporate almost instantly on creation. (What is an Instagram story, but a memorial to a good time?) Before the creation of digital photography there was, at least, something physical to hold on to. Benjamin’s point is particularly apt, and this whole system is particularly frail.

As an image based society, we are faced with our own image and legacy in ways inconceivable to past generations. We are always thinking about what others think of us. What will they post when we’re gone? How do we dress when we are effectively creating our own obituary? How do we dress for our own death? How do we dress when we know our children are going to record TikTok hauls of our closet? If photography preserves death, fashion lives—it is a conduit to the other side, an Ouija board connecting us to the past and the future. Acknowledging our specter, and dressing for its preservation, becomes the next step in the lineage of image.

Speaking of the whole what-will-they-post-when-we-are-gone persuasion, have you seen that the new AI thingy that will post after we die was patented?

Any excuse to mention how cooked we are. Sorry. Loved the post! As usual.

X

obsessed w you