How to Be a Creative Director

It’s as easy as downloading the Virgil Abloh Operating System.

During my summer vacation, I wrote the foreword for the new book The Virgil Reader: Volume 001, which accompanies the new exhibition at the Grand Palais “Virgil Abloh: The Codes.” You can find the book here, but it will probably sell out in a millisecond, so I wanted to share my foreword here so anyone can read it.

(Quick thing about the book: it is ingeniously designed as a university-style course reader with scans of Abloh’s interviews, including two of mine as well as an iconic conversation between Abloh and the artist Arthur Jafa from i-D.)

In a brief four year span before his unexpected passing, I interviewed Abloh more than half a dozen times. Twice for this profile in 032c (which served as a manifesto for his pre-LV era). Then again for 032c right after the Berlin Marathon in conversation with the runner Eluid Kipchoge. Then again in conversation with Young Thug for the cover of Interview magazine. Then again several times over for this GQ oral history that included interviews with 39 of his friends and collaborators. Thank you Conde Nast for footing the $5000+ transcription bill on that one ;)

Nearly half a decade later, I still think about Abloh at least once during every fashion week. Not just because he singlehandedly brought an entirely new audience to fashion (one that’s still there, btw), but also in the context of the pendulum swing from Streetwear to Quiet Luxury. During our first conversation Abloh compared Streetwear to Disco, and wondered out loud how the work he and his friends were doing would be remembered. What would his own pivot look like? Would he have flipped the script entirely and started making movies or buildings or megayachts? Would he be as active on Substack as he was on Clubhouse? That’s the thing about losing someone you know: Your memory of them can stay vivid, but what you really miss is how they would’ve experienced the present moment.

With the below text, I wanted to highlight the ways in which Abloh’s work constituted a system or way of working that I call the Virgil Abloh Operating System (VA.OS). And what’s important to me about this is that it’s very much a living blueprint that any aspiring creative person (or creative people in general) can learn and build from. So, without further interruption, my foreword on the VA.OS…

In his 1999 book Farewell to an Idea, the art historian T.J. Clark begins by speculating on what someone thousands of years ahead in the future might think about Modernism. If they were discovered without context, in complete archeological ruin, what might someone think about the works of Picasso, or Magritte, or Duchamp? What story might these charged and fractured artefacts tell about the society they were made in?

When it comes to the oeuvre of Virgil Abloh, it’s worth performing the same thought experiment. To this future archeological eye, would Abloh be a figure who primarily put words and quotation marks on products? Would he be thought of first and foremost as a Black man who broke barriers and achieved unprecedented success in a racist industry? Would he be thought of as an innovator who brought the artistic and architectural strategies of Modernism into fashion? Or could the evidence lead you to think he was perhaps a cult leader, one who commanded armies of fanatics to line up around city blocks for his merchandise and workshops?

I think about this question often now in terms of Abloh: It was only after his passing that it became evident to me that the six interviews we had done over the span of four years may have been messages in a bottle. Although he prided himself on having his own platform on which to directly communicate with his audience — “My brand was made from Instagram, not the pages of Vogue” — Abloh used interviews as a way of entering his philosophy into the public record. As he once explained to me, he had a very similar aim with his fashion shows: “[The] shows are more important to me than the clothes, because that’s the recorder. That’s the thing that records our existence as being part of fashion…This is about being part of history.” The very deliberate and pointed interviews Abloh gave me were not directed at luxury consumers or the fashion peanut gallery. They were intended for future generations. Rather than conveying his reality as a person or his intentions as an artist, what Abloh sought to communicate was an operating system. This systematic way of working — one that created a new blueprint for creativity in the era of late capitalism — was something he expressly intended to be open source and accessible to everyone. As he himself put it: “What I do has the instructions embedded into it, so that kids can look at the garment and think, ‘Hey, I can do that too.’”

Abloh did not want future archeologists to be confused about his oeuvre. In fact, he went to great lengths to make sure his practice was not only intelligible but replicable. Doing something “for the next generation” is a common platitude, but it’s actually rare to find practitioners offering a pointed guide on how to do what they did. (I’m not familiar with a Picasso interview on how to be a painter, or a Joan Didion interview on how to be a writer.) If one were to collect all of Abloh’s seminal interviews together in one volume (as this document starts to), the result would act as a textbook on how to be a creative director in the Internet age. Let’s call it the VA.OS. This printed reader is like a reflection of one of Abloh’s famous group chats, a living document that zeroes in on a creative philosophy, building itself through dialogue and constant questioning. To follow the VA.OS is not to repeat what it says, but to do as it does.

Before you download this operating system, remember that many of the tools for operating the VA.OS already exist on your phone:

Screenshot: Collating research, reference flipping, and copy-pasting were a central part of Abloh’s practice. They were also the main source of skepticism for those who criticized his work as being derivative or unoriginal. Copying as a form of making was a technique Abloh borrowed from contemporary art, drilling back through Conceptualism to Marcel Duchamp himself, who Abloh would describe as his “lawyer” in the face of plagiarism allegations. Like Duchamp, whose famous 1917 piece “Fountain” consisted of a urinal signed ‘R.Mutt’ and flipped upside down, the key to understanding Abloh’s readymades is to focus on the small gestures which both frame the original and alter its meaning. One also cannot discount the artistry of performing research and finding the right references. As Pusha T once said about Abloh: “His laptop was like a library of everything that was aesthetically beautiful and relevant.”

Caps Lock: Affixing words to an object, often in all-caps Helvetica, was a central tool in Abloh’s work, one that helped achieve the readymade effect mentioned above. As Abloh once told me: “Typography is the realm where you can unlock the reality of what a garment is. It’s Photoshop 3.0. If I take a men’s sweatshirt and write ‘woman’ on its back, that’s art.” Writing can fundamentally change an object without the object itself undergoing any other physical change. This use of words is a speech act: the designer is commenting on that which already exists. This was the central premise of Abloh’s famous double-quotation marks – to put something with a message in quotes causes the viewer to question everything about said thing. That’s just the power of punctuation, let alone words.

Share: Abloh’s rise coincided precisely with the rise of Instagram as the central conduit of contemporary fashion. Early on, at a time when legacy media did not yet recognize or respect his work, he used social media as his own PR apparatus, one in which he had a direct relationship with his audience without any middle man. While many fashion brands make clothes, then make images of clothes, then post those images to the Internet, Abloh’s practice vertically integrated all those steps. The garment was designed to be shareable from step one, long before it was seen in the 4:5 frame of a grid post. In this paradigm, the designer is not someone who stays in an atelier cutting dresses, but rather an image-maker and chief propagandist for their brand.

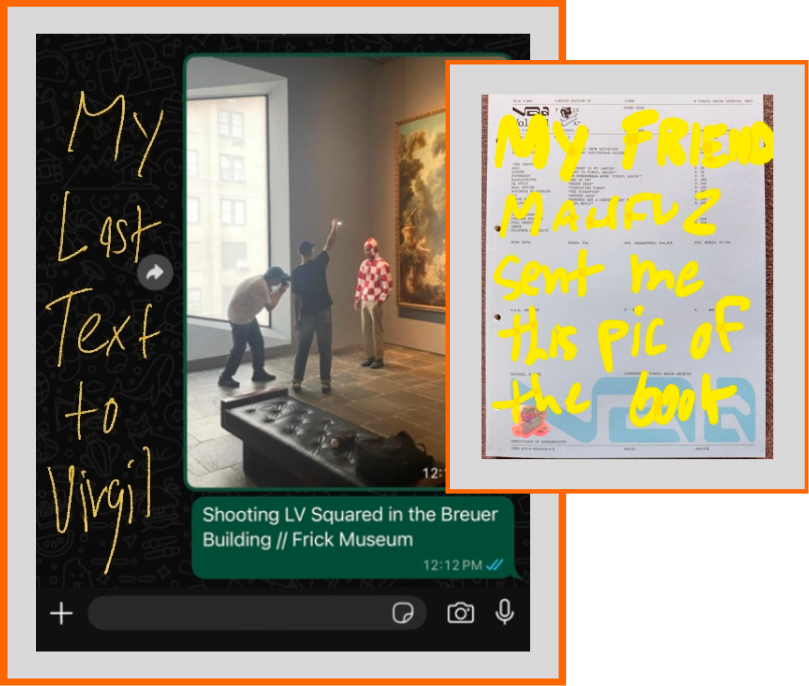

Group Chat: If Instagram was the front end of Abloh’s fashion machine, then Whatsapp was the back end. All those who conversed with him will remember his Whatsapp bio: “Typing…”, which imitated the in-app notice that someone was writing, which Abloh was indeed doing constantly. Group chats served as a management tool, a crit circle, a news source, and perhaps most importantly a means for stitching together a collaborative way of working. This wasn’t always collaborations in the This x That branding sense (although that did transpire a lot), but also extended to collaborations between experts and ideas people, manufacturers and designers, companies and artists. Chat was the creative glue of Abloh’s operation but also a chief principle that defined his process, one that was performed collectively and lived aloud.

Thom Bettridge is the Editor-in-Chief of i-D. In his spare time, he writes a newsletter about content called … CONTENT.

I’m still hopelessly addicted to Substack: Tish, Biz, and Sean do my favorite ones.

My life partner wouldn’t let me bring this gigantic oversized waterproof bag to Paris Fashion Week.

If you still haven’t read our 12,000-word Telfar Oral History, you’re chopped and washed and cooked.

The most joyous part of my month: Watching our teenage cover star Enza Khoury walk in all the big London Fashion Week shows.

i-D’s Steff Yotka says my iPad drawings (above) are “Unc Art.” If you’re my friend, please flame her in the comments.

“thats the thing with losing someone. Your memory of them can stay vivid but what you really miss is how they would experience the present moment” word wordd

I have so much respect for this -

"Abloh did not want future archeologists to be confused about his oeuvre. In fact, he went to great lengths to make sure his practice was not only intelligible but replicable. Doing something “for the next generation” is a common platitude, but it’s actually rare to find practitioners offering a pointed guide on how to do what they did."